MONDAY, Nov. 7, 2016 (HealthDay News) -- An antibody derived from the blood of Zika-infected people may have the potential to protect developing fetuses from the ravages of the virus, a new study with mice suggests.

The antibody, called ZIKV-117, protected fetal mice from a Zika infection in their pregnant mothers, said co-senior researcher Dr. James Crowe, director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Center in Nashville.

"The antibody treatment will clear the virus in the mother, but also protect the fetus, which is very important," Crowe said.

The antibody is only a short-term antiviral treatment, but the researchers said it demonstrates the potential of a Zika vaccine to provide people long-lasting immunity against the virus.

"No study so far has shown in any model that you could actually treat pregnant animals that are infected with Zika and protect the fetus," said co-senior researcher Dr. Michael Diamond, a professor of medicine and infectious diseases with Washington University in St. Louis. "This is the first study to do this, and it suggests that vaccines should work as well because vaccines induce antibody responses."

The researchers hope to proceed to human clinical trials for the antibody therapy within a year, Crowe said. They are currently making plans to test the antibody treatment in monkeys.

Zika virus produces a relatively mild infection in adults, with only one in every five people showing any symptoms at all, according to the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Instead, Zika poses the biggest health threat to the fetus. That's because the virus causes severe birth defects including microcephaly, where babies are born with too-small skulls and underdeveloped brains.

More than 2,000 children have been born with microcephaly or birth defects of the central nervous system in Brazil, the nexus of the Zika outbreak in South America, according to the World Health Organization.

To find a treatment for Zika, Crowe and his colleagues isolated antibody-producing immune cells from the blood of three people who previously had been infected with the virus.

From those immune system cells, the researchers obtained and then screened 29 different anti-Zika antibodies.

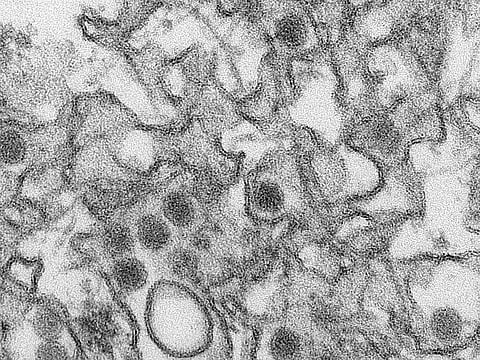

Lab tests showed that one of the antibodies, ZIKV-117, efficiently neutralized five different Zika strains, which represents the worldwide diversity of the virus, the researchers said.

To see whether the antibody would work in living creatures, researchers injected it into dozens of pregnant mice either one day before or one day after they had been infected with Zika.

The antibody markedly reduced the amount of Zika virus in the blood and brain tissues of the pregnant mice, and also reduced the levels of virus found in the placenta and the brain of the unborn fetus, researchers found.

In most cases, the antibodies were 95 to 100 percent protective of the fetus, Crowe said.

"The placenta did not get damaged, and the fetuses looked normal relative to uninfected animals," said Diamond.

The research team is working with the U.S. government and private companies about ways to support rapid development of the antiviral treatment, Crowe added.

The study is "important proof-of-concept that certain antibodies generated during Zika infection can be protective of a developing fetus," said Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior associate with the University of Pittsburgh's UPMC Center for Health Security.

"If this study, done in mice, can be replicated in other human models and the antibody developed for commercial use it could be an important way to mitigate the damage Zika causes," Adalja added.

However, studies conducted in animals often fail to pan out in human trials. And future tests will need to better reflect the real-world situation of most Zika-infected people, Adalja noted.

"In the study, antibody was administered very rapidly after laboratory infection, which would not be the norm with human cases, most of which will be asymptomatic," he said. "However, the study is important and paves the way for possible countermeasures to be used against Zika."

The findings were published Nov. 7 in the journal Nature.

More information

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides more information on mosquito-borne diseases.

This Q & A will tell you what you need to know about Zika.

To see the CDC list of sites where Zika virus is active and may pose a threat to pregnant women, click here.